[Washington Window] Considering the Diocese of Washington’s companion relationship with the Diocese of Honduras, it’s easy to see it in terms of giving and getting, of having and having not.

But to look at the 19-year partnership through that lens is to completely miss the point, members of this diocese’s Honduras Committee say.

Much has been said about the ‘mutual’ nature of relationships between dioceses, and Anglican Communion guidelines even go as far as to spell out the need to avoid “any tendency or temptation for the ‘North’ to designate or the ‘South’ to solicit financial aid.”

So what is it, exactly – if not the fuzzy “doing good for those less fortunate” feeling – that parishioners from this diocese take home with them from Honduras?

St. Mark’s, Capitol Hill parishioner and Honduras Committee member Betsy Agle has led five trips to the small Central American country – mostly youth groups – and says a tiny seed is planted in people when they visit.

“It’s a seed that’s planted deeply,” she says. “You don’t see so much about it, but it’s there.”

At a minimum, she says, the experience offers a look at the way others live.

In sharp contrast to life in the affluent United States, Honduras Committee member and Ascension, Silver Spring parishioner Dick Marks explains, “the family incomes are extremely low. The average daily wage of an agricultural worker is about $3 – and even in Honduras, that doesn’t buy very much.”

Electricity is not universally available, and some communities still rely on wells for their water, he says. People live close to the land, subsisting on locally raised corn and beans. Streets are largely unpaved, and in the rainy season, roads to many rural communities are “mostly impassable.”

In any case, Agle says, public transport is limited and “there’s very little money to travel. As [children] grow up, their village is very much their life, their horizon. The known world is smaller.”

And to the surprise of many U.S. teenagers, most kids their age are already working.

“I think it’s fundamentally different from anything they ever imagined, and that’s what the power of it is,” Agle says. “The conditions people live in are very different – fundamentally different – but it doesn’t mean they are different.

“I think the teens come back with a different sense of the richness of life that’s not so bound up in material things. They go back and they talk about the excess of things they have. Or things that momentarily seemed so important – cars and things – don’t seem so important any more.”

Also, she says, “it’s moving to make connections that are not based on somebody serving you – giving you a tourist service or something – but simply working alongside someone.”

Beyond gaining a new perspective, teens sometimes return with more than just a change in attitude or outlook, Agle says – in some cases, their lives literally change course.

Upon their return, many focus intently on learning or improving their Spanish. Some pay more attention to or decide to get involved with political and social issues like foreign aid and immigration.

It’s not just youth who are affected by visiting Honduras, says Collie Agle, who serves with his wife on the committee: adults also find the experience transformative.

“It really is an awakening,” he says. “Particularly being aware of the larger world. It’s so easy for us to be so insular.”

Most of his fellow parishioners lead busy lives, he says; raising kids, working long hours, saving for college. And “being in Washington these days – for me – is an overall depressing experience. I find that going down to Honduras, being with different people in a different culture that has a different outlook – it’s almost like a spiritual massage.”

Agle finds the “overt spirituality” of the familiar yet foreign Episcopal liturgy refreshing and the joyfulness and accessibility of the worship uplifting.

“I’m always reminded of the Franciscan attitude – that they’re carrying the church around on their back,” he says. “They don’t need a church structure to worship.” Many churches don’t have hymnals, for example, and the music is provided using a folk guitar: “A lot of people can get into it very easily. It sort of has an evangelical joyousness to it.”

Marks, who has visited Honduras six times since 2003, reports that fellow travelers often describe attending church in Honduras as one of the highlights of their trip.

“It revitalizes their faith,” he says. “It takes them away from what they’re used to on a Sunday and gives them a little more spiritual focus. … You’re forced to reset and you think more about what it really means.”

Marks finds that in Honduras his own worship experience is more meaningful, in part because life there is simpler, closer to the earth – much as it was in Jesus’ time.

“The conditions down there are more like the conditions in the Bible,” he says. Watching people reaping and sowing, worshiping and drawing water, the parables Jesus told spring to life and leap off the page.

Whatever it is – spiritual awakening, friendships forged, the satisfaction of doing good work – there’s something powerful about experiencing God in another place.

“I suppose in many respects, adults and kids come back,” says Collie Agle. “Like the little mustard seed: It may grow, it may remain dormant, but it’s always there.”

Note: This story was part of a package of stories on the Episcopal Diocese of Washington’s ongoing companion relationship with the Episcopal Diocese of Honduras.

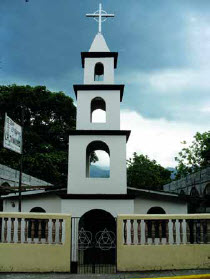

Teenagers from St. Mark’s, Capitol Hill, traveled to Trinidad, Honduras, in June 2006, where they planted trees as part of a reforestation program and made friends with local children [Photo courtesy of St. Mark’s, Capitol Hill].